Quark

A proton, composed of two up quarks and one down quark. (The color assignment of individual quarks is not important, only that all three colors are present.) |

|

| Composition | Elementary particle |

|---|---|

| Statistics | Fermionic |

| Generation | 1st, 2nd, 3rd |

| Interactions | Electromagnetism, Gravitation, Strong, Weak |

| Symbol | q |

| Antiparticle | Antiquark (q) |

| Theorized | Murray Gell-Mann (1964) George Zweig (1964) |

| Discovered | SLAC (~1968) |

| Types | 6 (up, down, strange, charm, bottom, and top) |

| Electric charge | +2⁄3 e, −1⁄3 e |

| Color charge | Yes |

| Spin | 1⁄2 |

| Baryon number | 1⁄3 |

A quark ( /ˈkwɔrk/ or /ˈkwɑrk/) is an elementary particle and a fundamental constituent of matter. Quarks combine to form composite particles called hadrons, the most stable of which are protons and neutrons, the components of atomic nuclei.[1] Due to a phenomenon known as color confinement, quarks are never directly observed or found in isolation; they can only be found within baryons or mesons.[2][3] For this reason, much of what is known about quarks has been drawn from observations of the hadrons themselves.

There are six types of quarks, known as flavors: up, down, strange, charm, bottom, and top.[4] Up and down quarks have the lowest masses of all quarks. The heavier quarks rapidly change into up and down quarks through a process of particle decay: the transformation from a higher mass state to a lower mass state. Because of this, up and down quarks are generally stable and the most common in the universe, whereas strange, charm, top, and bottom quarks can only be produced in high energy collisions (such as those involving cosmic rays and in particle accelerators).

Quarks have various intrinsic properties, including electric charge, color charge, spin, and mass. Quarks are the only elementary particles in the Standard Model of particle physics to experience all four fundamental interactions, also known as fundamental forces (electromagnetism, gravitation, strong interaction, and weak interaction), as well as the only known particles whose electric charges are not integer multiples of the elementary charge. For every quark flavor there is a corresponding type of antiparticle, known as antiquark, that differs from the quark only in that some of its properties have equal magnitude but opposite sign.

The quark model was independently proposed by physicists Murray Gell-Mann and George Zweig in 1964.[5] Quarks were introduced as parts of an ordering scheme for hadrons, and there was little evidence for their physical existence until deep inelastic scattering experiments at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center in 1968.[6][7] All six flavors of quark have since been observed in accelerator experiments; the top quark, first observed at Fermilab in 1995, was the last to be discovered.[5]

Contents |

Classification

The Standard Model is the theoretical framework describing all the currently known elementary particles, as well as the unobserved[nb 1] Higgs boson.[8] This model contains six flavors of quarks (q), named up (u), down (d), strange (s), charm (c), bottom (b), and top (t).[4] Antiparticles of quarks are called antiquarks, and are denoted by a bar over the symbol for the corresponding quark, such as u for an up antiquark. As with antimatter in general, antiquarks have the same mass, mean lifetime, and spin as their respective quarks, but the electric charge and other charges have the opposite sign.[9]

Quarks are spin-1⁄2 particles, implying that they are fermions according to the spin-statistics theorem. They are subject to the Pauli exclusion principle, which states that no two identical fermions can simultaneously occupy the same quantum state. This is in contrast to bosons (particles with integer spin), any number of which can be in the same state.[10] Unlike leptons, quarks possess color charge, which causes them to engage in the strong interaction. The resulting attraction between different quarks causes the formation of composite particles known as hadrons (see "Strong interaction and color charge" below).

The quarks which determine the quantum numbers of hadrons are called valence quarks; apart from these, any hadron may contain an indefinite number of virtual (or sea) quarks, antiquarks, and gluons which do not influence its quantum numbers.[11] There are two families of hadrons: baryons, with three valence quarks, and mesons, with a valence quark and an antiquark.[12] The most common baryons are the proton and the neutron, the building blocks of the atomic nucleus.[13] A great number of hadrons are known (see list of baryons and list of mesons), most of them differentiated by their quark content and the properties these constituent quarks confer. The existence of "exotic" hadrons with more valence quarks, such as tetraquarks (qqqq) and pentaquarks (qqqqq), has been conjectured[14] but not proven.[nb 2][14][15]

Elementary fermions are grouped into three generations, each comprising two leptons and two quarks. The first generation includes up and down quarks, the second strange and charm quarks, and the third bottom and top quarks. All searches for a fourth generation of quarks and other elementary fermions have failed,[16] and there is strong indirect evidence that no more than three generations exist.[nb 3][17] Particles in higher generations generally have greater mass and less stability, causing them to decay into lower-generation particles by means of weak interactions. Only first-generation (up and down) quarks occur commonly in nature. Heavier quarks can only be created in high-energy collisions (such as in those involving cosmic rays), and decay quickly; however, they are thought to have been present during the first fractions of a second after the Big Bang, when the universe was in an extremely hot and dense phase (the quark epoch). Studies of heavier quarks are conducted in artificially created conditions, such as in particle accelerators.[18]

Having electric charge, mass, color charge, and flavor, quarks are the only known elementary particles that engage in all four fundamental interactions of contemporary physics: electromagnetism, gravitation, strong interaction, and weak interaction.[13] Gravitation is too weak to be relevant to individual particle interactions except at extremes of energy (Planck energy) and distance scales (Planck distance). However, since no successful quantum theory of gravity exists, gravitation is not described by the Standard Model.

See the table of properties below for a more complete overview of the six quark flavors' properties.

History

The quark model was independently proposed by physicists Murray Gell-Mann[19] and George Zweig[20][21] in 1964.[5] The proposal came shortly after Gell-Mann's 1961 formulation of a particle classification system known as the Eightfold Way—or, in more technical terms, SU(3) flavor symmetry.[22] Physicist Yuval Ne'eman had independently developed a scheme similar to the Eightfold Way in the same year.[23][24]

At the time of the quark theory's inception, the "particle zoo" included, amongst other particles, a multitude of hadrons. Gell-Mann and Zweig posited that they were not elementary particles, but were instead composed of combinations of quarks and antiquarks. Their model involved three flavors of quarks—up, down, and strange—to which they ascribed properties such as spin and electric charge.[19][20][21] The initial reaction of the physics community to the proposal was mixed. There was particular contention about whether the quark was a physical entity or an abstraction used to explain concepts that were not properly understood at the time.[25]

In less than a year, extensions to the Gell-Mann–Zweig model were proposed. Sheldon Lee Glashow and James Bjorken predicted the existence of a fourth flavor of quark, which they called charm. The addition was proposed because it allowed for a better description of the weak interaction (the mechanism that allows quarks to decay), equalized the number of known quarks with the number of known leptons, and implied a mass formula that correctly reproduced the masses of the known mesons.[26]

In 1968, deep inelastic scattering experiments at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC) showed that the proton contained much smaller, point-like objects and was therefore not an elementary particle.[6][7][27] Physicists were reluctant to identify these objects with quarks at the time, instead calling them "partons"—a term coined by Richard Feynman.[28][29][30] The objects that were observed at the SLAC would later be identified as up and down quarks as the other flavors were discovered.[31] Nevertheless, "parton" remains in use as a collective term for the constituents of hadrons (quarks, antiquarks, and gluons).

The strange quark's existence was indirectly validated by the SLAC's scattering experiments: not only was it a necessary component of Gell-Mann and Zweig's three-quark model, but it provided an explanation for the kaon (K) and pion (π) hadrons discovered in cosmic rays in 1947.[32]

In a 1970 paper, Glashow, John Iliopoulos and Luciano Maiani presented further reasoning for the existence of the as-yet undiscovered charm quark.[33][34] The number of supposed quark flavors grew to the current six in 1973, when Makoto Kobayashi and Toshihide Maskawa noted that the experimental observation of CP violation[nb 4][35] could be explained if there were another pair of quarks.

Charm quarks were produced almost simultaneously by two teams in November 1974 (see November Revolution)—one at the SLAC under Burton Richter, and one at Brookhaven National Laboratory under Samuel Ting. The charm quarks were observed bound with charm antiquarks in mesons. The two parties had assigned the discovered meson two different symbols, J and ψ; thus, it became formally known as the J/ψ meson. The discovery finally convinced the physics community of the quark model's validity.[30]

In the following years a number of suggestions appeared for extending the quark model to six quarks. Of these, the 1975 paper by Haim Harari[36] was the first to coin the terms top and bottom for the additional quarks.[37]

In 1977, the bottom quark was observed by a team at Fermilab led by Leon Lederman.[38][39] This was a strong indicator of the top quark's existence: without the top quark, the bottom quark would have been without a partner. However, it was not until 1995 that the top quark was finally observed, also by the CDF[40] and DØ[41] teams at Fermilab.[5] It had a mass much greater than had been previously expected[42]—almost as great as a gold atom.[43]

Etymology

For some time, Gell-Mann was undecided on an actual spelling for the term he intended to coin, until he found the word quark in James Joyce's book Finnegans Wake:

Three quarks for Muster Mark!

Sure he has not got much of a bark

And sure any he has it's all beside the mark.—James Joyce, Finnegans Wake[44]

Gell-Mann went into further detail regarding the name of the quark in his book, The Quark and the Jaguar:[45]

| “ | In 1963, when I assigned the name "quark" to the fundamental constituents of the nucleon, I had the sound first, without the spelling, which could have been "kwork". Then, in one of my occasional perusals of Finnegans Wake, by James Joyce, I came across the word "quark" in the phrase "Three quarks for Muster Mark". Since "quark" (meaning, for one thing, the cry of the gull) was clearly intended to rhyme with "Mark", as well as "bark" and other such words, I had to find an excuse to pronounce it as "kwork". But the book represents the dream of a publican named Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker. Words in the text are typically drawn from several sources at once, like the "portmanteau" words in "Through the Looking-Glass". From time to time, phrases occur in the book that are partially determined by calls for drinks at the bar. I argued, therefore, that perhaps one of the multiple sources of the cry "Three quarks for Muster Mark" might be "Three quarts for Mister Mark", in which case the pronunciation "kwork" would not be totally unjustified. In any case, the number three fitted perfectly the way quarks occur in nature. | ” |

Zweig preferred the name ace for the particle he had theorized, but Gell-Mann's terminology came to prominence once the quark model had been commonly accepted.[46]

The quark flavors were given their names for a number of reasons. The up and down quarks are named after the up and down components of isospin, which they carry.[47] Strange quarks were given their name because they were discovered to be components of the strange particles discovered in cosmic rays years before the quark model was proposed; these particles were deemed "strange" because they had unusually long lifetimes.[48] Glashow, who coproposed charm quark with Bjorken, is quoted as saying, "We called our construct the 'charmed quark', for we were fascinated and pleased by the symmetry it brought to the subnuclear world."[49] The names "bottom" and "top", coined by Harari, were chosen because they are "logical partners for up and down quarks".[36][37][48] In the past, bottom and top quarks were sometimes referred to as "beauty" and "truth" respectively, but these names have somewhat fallen out of use.[50] While "truth" never did catch on, accelerator complexes devoted to massive production of bottom quarks are sometimes called "beauty factories".[51]

Properties

Electric charge

Quarks have fractional electric charge values—either 1⁄3 or 2⁄3 times the elementary charge, depending on flavor. Up, charm, and top quarks (collectively referred to as up-type quarks) have a charge of +2⁄3, while down, strange, and bottom quarks (down-type quarks) have −1⁄3. Antiquarks have the opposite charge to their corresponding quarks; up-type antiquarks have charges of −2⁄3 and down-type antiquarks have charges of +1⁄3. Since the electric charge of a hadron is the sum of the charges of the constituent quarks, all hadrons have integer charges: the combination of three quarks (baryons), three antiquarks (antibaryons), or a quark and an antiquark (mesons) always results in integer charges.[52] For example, the hadron constituents of atomic nuclei, neutrons and protons, have charges of 0 and +1 respectively; the neutron is composed of two down quarks and one up quark, and the proton of two up quarks and one down quark.[13]

Spin

Spin is an intrinsic property of elementary particles, and its direction is an important degree of freedom. It is sometimes visualized as the rotation of an object around its own axis (hence the name "spin"), though this notion is somewhat misguided at subatomic scales because elementary particles are believed to be point-like.[53]

Spin can be represented by a vector whose length is measured in units of the reduced Planck constant ħ (pronounced "h bar"). For quarks, a measurement of the spin vector component along any axis can only yield the values +ħ/2 or −ħ/2; for this reason quarks are classified as spin-1⁄2 particles.[54] The component of spin along a given axis—by convention the z axis—is often denoted by an up arrow ↑ for the value +1⁄2 and down arrow ↓ for the value −1⁄2, placed after the symbol for flavor. For example, an up quark with a spin of +1⁄2 along the z axis is denoted by u↑.[55]

Weak interaction

A quark of one flavor can transform into a quark of another flavor only through the weak interaction, one of the four fundamental interactions in particle physics. By absorbing or emitting a W boson, any up-type quark (up, charm, and top quarks) can change into any down-type quark (down, strange, and bottom quarks) and vice versa. This flavor transformation mechanism causes the radioactive process of beta decay, in which a neutron (n) "splits" into a proton (p), an electron (e−

) and an electron antineutrino (ν

e) (see picture). This occurs when one of the down quarks in the neutron (udd) decays into an up quark by emitting a virtual W−

boson, transforming the neutron into a proton (uud). The W−

boson then decays into an electron and an electron antineutrino.[56]

| n | → | p | + | e− |

+ | ν e |

(Beta decay, hadron notation) |

| udd | → | uud | + | e− |

+ | ν e |

(Beta decay, quark notation) |

Both beta decay and the inverse process of inverse beta decay are routinely used in medical applications such as positron emission tomography (PET) and in high-energy experiments such as neutrino detection.

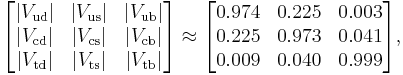

While the process of flavor transformation is the same for all quarks, each quark has a preference to transform into the quark of its own generation. The relative tendencies of all flavor transformations are described by a mathematical table, called the Cabibbo–Kobayashi–Maskawa matrix (CKM matrix). The approximate magnitudes of the entries of the CKM matrix are:[57]

where Vij represents the tendency of a quark of flavor i to change into a quark of flavor j (or vice versa).[nb 5]

There exists an equivalent weak interaction matrix for leptons (right side of the W boson on the above beta decay diagram), called the Pontecorvo–Maki–Nakagawa–Sakata matrix (PMNS matrix).[58] Together, the CKM and PMNS matrices describe all flavor transformations, but the links between the two are not yet clear.[59]

Strong interaction and color charge

Quarks possess a property called color charge. There are three types of color charge, arbitrarily labeled blue, green, and red.[nb 6] Each of them is complemented by an anticolor—antiblue, antigreen, and antired. Every quark carries a color, while every antiquark carries an anticolor.[60]

The system of attraction and repulsion between quarks charged with different combinations of the three colors is called strong interaction, which is mediated by force carrying particles known as gluons; this is discussed at length below. The theory that describes strong interactions is called quantum chromodynamics (QCD). A quark charged with one color value can form a bound system with an antiquark carrying the corresponding anticolor; three (anti)quarks, one of each (anti)color, will similarly be bound together. The result of two attracting quarks will be color neutrality: a quark with color charge ξ plus an antiquark with color charge −ξ will result in a color charge of 0 (or "white" color) and the formation of a meson. Analogous to the additive color model in basic optics, the combination of three quarks or three antiquarks, each with different color charges, will result in the same "white" color charge and the formation of a baryon or antibaryon.[61]

In modern particle physics, gauge symmetries—a kind of symmetry group—relate interactions between particles (see gauge theories). Color SU(3) (commonly abbreviated to SU(3)c) is the gauge symmetry that relates the color charge in quarks and is the defining symmetry for quantum chromodynamics.[62] Just as the laws of physics are independent of which directions in space are designated x, y, and z, and remain unchanged if the coordinate axes are rotated to a new orientation, the physics of quantum chromodynamics is independent of which directions in three-dimensional color space are identified as blue, red, and green. SU(3)c color transformations correspond to "rotations" in color space (which, mathematically speaking, is a complex space). Every quark flavor f, each with subtypes fB, fG, fR corresponding to the quark colors,[63] forms a triplet: a three-component quantum field which transforms under the fundamental representation of SU(3)c.[64] The requirement that SU(3)c should be local—that is, that its transformations be allowed to vary with space and time—determines the properties of the strong interaction, in particular the existence of eight gluon types to act as its force carriers.[62][65]

Mass

Two terms are used in referring to a quark's mass: current quark mass refers to the mass of a quark by itself, while constituent quark mass refers to the current quark mass plus the mass of the gluon particle field surrounding the quark.[66] These masses typically have very different values. Most of a hadron's mass comes from the gluons that bind the constituent quarks together, rather than from the quarks themselves. While gluons are inherently massless, they possess energy—more specifically, quantum chromodynamics binding energy (QCBE)—and it is this that contributes so greatly to the overall mass of the hadron (see mass in special relativity). For example, a proton has a mass of approximately 938 MeV/c2, of which the rest mass of its three valence quarks only contributes about 11 MeV/c2; much of the remainder can be attributed to the gluons' QCBE.[67][68]

The Standard Model posits that elementary particles derive their masses from the Higgs mechanism, which is related to the unobserved Higgs boson. Physicists hope that further research into the reasons for the top quark's large mass, which was found to be approximately equal to that of a gold nucleus (~171 GeV/c2),[67][69] might reveal more about the origin of the mass of quarks and other elementary particles.[70]

Table of properties

The following table summarizes the key properties of the six quarks. Flavor quantum numbers (isospin (I3), charm (C), strangeness (S, not to be confused with spin), topness (T), and bottomness (B′)) are assigned to certain quark flavors, and denote qualities of quark-based systems and hadrons. The baryon number (B) is +1⁄3 for all quarks, as baryons are made of three quarks. For antiquarks, the electric charge (Q) and all flavor quantum numbers (B, I3, C, S, T, and B′) are of opposite sign. Mass and total angular momentum (J; equal to spin for point particles) do not change sign for the antiquarks.

| Name | Symbol | Mass (MeV/c2)* | J | B | Q | I3 | C | S | T | B′ | Antiparticle | Antiparticle symbol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First generation | ||||||||||||

| Up | u | 1.7 to 3.3 | 1⁄2 | +1⁄3 | +2⁄3 | +1⁄2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Antiup | u |

| Down | d | 4.1 to 5.8 | 1⁄2 | +1⁄3 | −1⁄3 | −1⁄2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Antidown | d |

| Second generation | ||||||||||||

| Charm | c | 1,270+70 −90 |

1⁄2 | +1⁄3 | +2⁄3 | 0 | +1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Anticharm | c |

| Strange | s | 101+29 −21 |

1⁄2 | +1⁄3 | −1⁄3 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | Antistrange | s |

| Third generation | ||||||||||||

| Top | t | 172,000±900 ±1,300 | 1⁄2 | +1⁄3 | +2⁄3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | +1 | 0 | Antitop | t |

| Bottom | b | 4,190+180 −60 |

1⁄2 | +1⁄3 | −1⁄3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | Antibottom | b |

* Notation such as 4,190+180

−60 denotes measurement uncertainty. In the case of the top quark, the first uncertainty is statistical in nature, and the second is systematic.

Interacting quarks

As described by quantum chromodynamics, the strong interaction between quarks is mediated by gluons, massless vector gauge bosons. Each gluon carries one color charge and one anticolor charge. In the standard framework of particle interactions (part of a more general formulation known as perturbation theory), gluons are constantly exchanged between quarks through a virtual emission and absorption process. When a gluon is transferred between quarks, a color change occurs in both; for example, if a red quark emits a red–antigreen gluon, it becomes green, and if a green quark absorbs a red–antigreen gluon, it becomes red. Therefore, while each quark's color constantly changes, their strong interaction is preserved.[71][72][73]

Since gluons carry color charge, they themselves are able to emit and absorb other gluons. This causes asymptotic freedom: as quarks come closer to each other, the chromodynamic binding force between them weakens.[74] Conversely, as the distance between quarks increases, the binding force strengthens. The color field becomes stressed, much as an elastic band is stressed when stretched, and more gluons of appropriate color are spontaneously created to strengthen the field. Above a certain energy threshold, pairs of quarks and antiquarks are created. These pairs bind with the quarks being separated, causing new hadrons to form. This phenomenon is known as color confinement: quarks never appear in isolation.[72][75] This process of hadronization occurs before quarks, formed in a high energy collision, are able to interact in any other way. The only exception is the top quark, which may decay before it hadronizes.[76]

Sea quarks

Hadrons, along with the valence quarks (q

v) that contribute to their quantum numbers, contain virtual quark–antiquark (qq) pairs known as sea quarks (q

s). Sea quarks form when a gluon of the hadron's color field splits; this process also works in reverse in that the annihilation of two sea quarks produces a gluon. The result is a constant flux of gluon splits and creations colloquially known as "the sea".[77] Sea quarks are much less stable than their valence counterparts, and they typically annihilate each other within the interior of the hadron. Despite this, sea quarks can hadronize into baryonic or mesonic particles under certain circumstances.[78]

Other phases of quark matter

Under sufficiently extreme conditions, quarks may become deconfined and exist as free particles. In the course of asymptotic freedom, the strong interaction becomes weaker at higher temperatures. Eventually, color confinement would be lost and an extremely hot plasma of freely moving quarks and gluons would be formed. This theoretical phase of matter is called quark–gluon plasma.[81] The exact conditions needed to give rise to this state are unknown and have been the subject of a great deal of speculation and experimentation. A recent estimate puts the needed temperature at 1.90±0.02×1012 kelvin.[82] While a state of entirely free quarks and gluons has never been achieved (despite numerous attempts by CERN in the 1980s and 1990s),[83] recent experiments at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider have yielded evidence for liquid-like quark matter exhibiting "nearly perfect" fluid motion.[84]

The quark–gluon plasma would be characterized by a great increase in the number of heavier quark pairs in relation to the number of up and down quark pairs. It is believed that in the period prior to 10−6 seconds after the Big Bang (the quark epoch), the universe was filled with quark–gluon plasma, as the temperature was too high for hadrons to be stable.[85]

Given sufficiently high baryon densities and relatively low temperatures—possibly comparable to those found in neutron stars—quark matter is expected to degenerate into a Fermi liquid of weakly interacting quarks. This liquid would be characterized by a condensation of colored quark Cooper pairs, thereby breaking the local SU(3)c symmetry. Because quark Cooper pairs harbor color charge, such a phase of quark matter would be color superconductive; that is, color charge would be able to pass through it with no resistance.[86]

See also

| Book: Quarks

Book: Particles of the Standard Model Book: Hadronic Matter |

|

| Wikipedia books are collections of articles that can be downloaded or ordered in print. | |

- Color–flavor locking

- Quarkonium – Mesons made of a quark and antiquark of the same flavor

- Preons – Hypothetical particles which were once postulated to be subcomponents of quarks and leptons

- Quark–lepton complementarity – Possible fundamental relation between quarks and leptons

- Quark star – A hypothetical degenerate neutron star with extreme density

- Neutron magnetic moment

Notes

- ^ As of November 2011[update].

- ^ Several research groups claimed to have proven the existence of tetraquarks and pentaquarks in the early 2000s. While the status of tetraquarks is still under debate, all known pentaquark candidates have since been established as non-existent.

- ^ The main evidence is based on the resonance width of the Z0

boson, which constrains the 4th generation neutrino to have a mass greater than ~45 GeV/c2. This would be highly contrasting with the other three generations' neutrinos, whose masses cannot exceed 2 MeV/c2. - ^ CP violation is a phenomenon which causes weak interactions to behave differently when left and right are swapped (P symmetry) and particles are replaced with their corresponding antiparticles (C symmetry).

- ^ The actual probability of decay of one quark to another is a complicated function of (amongst other variables) the decaying quark's mass, the masses of the decay products, and the corresponding element of the CKM matrix. This probability is directly proportional (but not equal) to the magnitude squared (|Vij|2) of the corresponding CKM entry.

- ^ Despite its name, color charge is not related to the color spectrum of visible light.

References

- ^ "Quark (subatomic particle)". Encyclopædia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/486323/quark. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ^ R. Nave. "Confinement of Quarks". HyperPhysics. Georgia State University, Department of Physics and Astronomy. http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/Particles/quark.html#c6. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ^ R. Nave. "Bag Model of Quark Confinement". HyperPhysics. Georgia State University, Department of Physics and Astronomy. http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/Particles/qbag.html#c1. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ^ a b R. Nave. "Quarks". HyperPhysics. Georgia State University, Department of Physics and Astronomy. http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/Particles/quark.html. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ^ a b c d B. Carithers, P. Grannis (1995). "Discovery of the Top Quark" (PDF). Beam Line (SLAC) 25 (3): 4–16. http://www.slac.stanford.edu/pubs/beamline/25/3/25-3-carithers.pdf. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ^ a b E.D. Bloom et al. (1969). "High-Energy Inelastic e–p Scattering at 6° and 10°". Physical Review Letters 23 (16): 930–934. Bibcode 1969PhRvL..23..930B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.23.930.

- ^ a b M. Breidenbach et al. (1969). "Observed Behavior of Highly Inelastic Electron–Proton Scattering". Physical Review Letters 23 (16): 935–939. Bibcode 1969PhRvL..23..935B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.23.935.

- ^ C. Amsler et al. (Particle Data Group) (2008). "Higgs Bosons: Theory and Searches". Physics Letters B 667 (1): 1–1340. Bibcode 2008PhLB..667....1P. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018. http://pdg.lbl.gov/2009/reviews/rpp2009-rev-higgs-boson.pdf.

- ^ S.S.M. Wong (1998). Introductory Nuclear Physics (2nd ed.). Wiley Interscience. p. 30. ISBN 0-471-23973-9.

- ^ K.A. Peacock (2008). The Quantum Revolution. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 125. ISBN 031333448X.

- ^ B. Povh, C. Scholz, K. Rith, F. Zetsche (2008). Particles and Nuclei. Springer. p. 98. ISBN 3540793674.

- ^ Section 6.1. in P.C.W. Davies (1979). The Forces of Nature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 052122523X.

- ^ a b c M. Munowitz (2005). Knowing. Oxford University Press. p. 35. ISBN 0195167376.

- ^ a b W.-M. Yao et al. (Particle Data Group) (2006). "Review of Particle Physics: Pentaquark Update". Journal of Physics G 33 (1): 1–1232. arXiv:astro-ph/0601168. Bibcode 2006JPhG...33....1Y. doi:10.1088/0954-3899/33/1/001. http://pdg.lbl.gov/2006/reviews/theta_b152.pdf.

- ^ C. Amsler et al. (Particle Data Group) (2008). "Review of Particle Physics: Pentaquarks". Physics Letters B 667 (1): 1–1340. Bibcode 2008PhLB..667....1P. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018. http://pdg.lbl.gov/2008/reviews/pentaquarks_b801.pdf.

C. Amsler et al. (Particle Data Group) (2008). "Review of Particle Physics: New Charmonium-Like States". Physics Letters B 667 (1): 1–1340. Bibcode 2008PhLB..667....1P. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018. http://pdg.lbl.gov/2008/reviews/rpp2008-rev-new-charmonium-like-states.pdf.

E.V. Shuryak (2004). The QCD Vacuum, Hadrons and Superdense Matter. World Scientific. p. 59. ISBN 9812385746. - ^ C. Amsler et al. (Particle Data Group) (2008). "Review of Particle Physics: b′ (4th Generation) Quarks, Searches for". Physics Letters B 667 (1): 1–1340. Bibcode 2008PhLB..667....1P. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018. http://pdg.lbl.gov/2008/listings/q008.pdf.

C. Amsler et al. (Particle Data Group) (2008). "Review of Particle Physics: t′ (4th Generation) Quarks, Searches for". Physics Letters B 667 (1): 1–1340. Bibcode 2008PhLB..667....1P. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018. http://pdg.lbl.gov/2008/listings/q009.pdf. - ^ D. Decamp (1989). "Determination of the number of light neutrino species". Physics Letters B 231 (4): 519. Bibcode 1989PhLB..231..519D. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(89)90704-1.

A. Fisher (1991). "Searching for the Beginning of Time: Cosmic Connection". Popular Science 238 (4): 70. http://books.google.com/?id=eyPfgGGTfGgC&pg=PA70&dq=quarks+no+more+than+three+generations.

J.D. Barrow (1997) [1994]. "The Singularity and Other Problems". The Origin of the Universe (Reprint ed.). Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465053148. - ^ D.H. Perkins (2003). Particle Astrophysics. Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 0198509529.

- ^ a b M. Gell-Mann (1964). "A Schematic Model of Baryons and Mesons". Physics Letters 8 (3): 214–215. Bibcode 1964PhL.....8..214G. doi:10.1016/S0031-9163(64)92001-3.

- ^ a b G. Zweig (1964). "An SU(3) Model for Strong Interaction Symmetry and its Breaking". CERN Report No.8182/TH.401. http://cdsweb.cern.ch/record/352337/files/CM-P00042883.pdf.

- ^ a b G. Zweig (1964). "An SU(3) Model for Strong Interaction Symmetry and its Breaking: II". CERN Report No.8419/TH.412. http://lib-www.lanl.gov/la-pubs/00323548.pdf.

- ^ M. Gell-Mann (2000) [1964]. "The Eightfold Way: A theory of strong interaction symmetry". In M. Gell-Manm, Y. Ne'emann. The Eightfold Way. Westview Press. p. 11. ISBN 0-7382-0299-1.

Original: M. Gell-Mann (1961). "The Eightfold Way: A theory of strong interaction symmetry". Synchroton Laboratory Report CTSL-20 (California Institute of Technology). - ^ Y. Ne'emann (2000) [1964]. "Derivation of strong interactions from gauge invariance". In M. Gell-Manm, Y. Ne'emann. The Eightfold Way. Westview Press. ISBN 0-7382-0299-1.

Original Y. Ne'emann (1961). "Derivation of strong interactions from gauge invariance". Nuclear Physics 26 (2): 222. Bibcode 1961NucPh..26..222N. doi:10.1016/0029-5582(61)90134-1. - ^ Companion to the History of Modern Science. Taylor & Francis. 1996. p. 673. ISBN 0415145783.

- ^ A. Pickering (1984). Constructing Quarks. University of Chicago Press. pp. 114–125. ISBN 0226667995.

- ^ B.J. Bjorken, S.L. Glashow (1964). "Elementary Particles and SU(4)". Physics Letters 11 (3): 255–257. Bibcode 1964PhL....11..255B. doi:10.1016/0031-9163(64)90433-0.

- ^ J.I. Friedman. "The Road to the Nobel Prize". Hue University. http://www.hueuni.edu.vn/hueuni/en/news_detail.php?NewsID=1606&PHPSESSID=909807ffc5b9c0288cc8d137ff063c72. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ R.P. Feynman (1969). "Very High-Energy Collisions of Hadrons". Physical Review Letters 23 (24): 1415–1417. Bibcode 1969PhRvL..23.1415F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.23.1415.

- ^ S. Kretzer et al. (2004). "CTEQ6 Parton Distributions with Heavy Quark Mass Effects". Physical Review D 69 (11): 114005. arXiv:hep-ph/0307022. Bibcode 2004PhRvD..69k4005K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.69.114005.

- ^ a b D.J. Griffiths (1987). Introduction to Elementary Particles. John Wiley & Sons. p. 42. ISBN 0-471-60386-4.

- ^ M.E. Peskin, D.V. Schroeder (1995). An introduction to quantum field theory. Addison–Wesley. p. 556. ISBN 0-201-50397-2.

- ^ V.V. Ezhela (1996). Particle physics. Springer. p. 2. ISBN 1563966425.

- ^ S.L. Glashow, J. Iliopoulos, L. Maiani (1970). "Weak Interactions with Lepton–Hadron Symmetry". Physical Review D 2 (7): 1285–1292. Bibcode 1970PhRvD...2.1285G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.2.1285.

- ^ D.J. Griffiths (1987). Introduction to Elementary Particles. John Wiley & Sons. p. 44. ISBN 0-471-60386-4.

- ^ M. Kobayashi, T. Maskawa (1973). "CP-Violation in the Renormalizable Theory of Weak Interaction". Progress of Theoretical Physics 49 (2): 652–657. Bibcode 1973PThPh..49..652K. doi:10.1143/PTP.49.652. http://ptp.ipap.jp/link?PTP/49/652/pdf.

- ^ a b H. Harari (1975). "A new quark model for hadrons". Physics Letters B 57B (3): 265. Bibcode 1975PhLB...57..265H. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(75)90072-6.

- ^ a b K.W. Staley (2004). The Evidence for the Top Quark. Cambridge University Press. pp. 31–33. ISBN 9780521827102. http://books.google.com/?id=K7z2oUBzB_wC.

- ^ S.W. Herb et al. (1997). "Observation of a Dimuon Resonance at 9.5 GeV in 400-GeV Proton-Nucleus Collisions". Physical Review Letters 39 (5): 252. Bibcode 1977PhRvL..39..252H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.39.252.

- ^ M. Bartusiak (1994). A Positron named Priscilla. National Academies Press. p. 245. ISBN 0309048931.

- ^ F. Abe et al. (CDF Collaboration) (1995). "Observation of Top Quark Production in pp Collisions with the Collider Detector at Fermilab". Physical Review Letters 74 (14): 2626–2631. Bibcode 1995PhRvL..74.2626A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.74.2626. PMID 10057978.

- ^ S. Abachi et al. (DØ Collaboration) (1995). "Search for High Mass Top Quark Production in pp Collisions at √s = 1.8 TeV". Physical Review Letters 74 (13): 2422–2426. Bibcode 1995PhRvL..74.2422A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.74.2422.

- ^ K.W. Staley (2004). The Evidence for the Top Quark. Cambridge University Press. p. 144. ISBN 0521827108. http://books.google.com/?id=K7z2oUBzB_wC.

- ^ "New Precision Measurement of Top Quark Mass". Brookhaven National Laboratory News. http://www.bnl.gov/bnlweb/pubaf/pr/PR_display.asp?prID=04-66. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

- ^ J. Joyce (1982) [1939]. Finnegans Wake. Penguin Books. p. 383. ISBN 0-14-00-6286-6. LCCN 59354.

- ^ M. Gell-Mann (1995). The Quark and the Jaguar: Adventures in the Simple and the Complex. Henry Holt and Co. p. 180. ISBN 978-0805072532.

- ^ J. Gleick (1992). Genius: Richard Feynman and modern physics. Little Brown and Company. p. 390. ISBN 0-316-903167.

- ^ J.J. Sakurai (1994). S.F Tuan. ed. Modern Quantum Mechanics (Revised ed.). Addison–Wesley. p. 376. ISBN 0-201-53929-2.

- ^ a b D.H. Perkins (2000). Introduction to high energy physics. Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 0521621968.

- ^ M. Riordan (1987). The Hunting of the Quark: A True Story of Modern Physics. Simon & Schuster. p. 210. ISBN 9780671504663.

- ^ F. Close (2006). The New Cosmic Onion. CRC Press. p. 133. ISBN 1584887982.

- ^ J.T. Volk et al. (1987). Letter of Intent for a Tevatron Beauty Factory. Fermilab Proposal #783. http://lss.fnal.gov/archive/test-proposal/0000/fermilab-proposal-0783.pdf.

- ^ G. Fraser (2006). The New Physics for the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 91. ISBN 0521816009.

- ^ "The Standard Model of Particle Physics". BBC. 2002. http://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/h2g2/A666173. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- ^ F. Close (2006). The New Cosmic Onion. CRC Press. pp. 80–90. ISBN 1584887982.

- ^ D. Lincoln (2004). Understanding the Universe. World Scientific. p. 116. ISBN 9812387056.

- ^ "Weak Interactions". Virtual Visitor Center. Stanford Linear Accelerator Center. 2008. http://www2.slac.stanford.edu/vvc/theory/weakinteract.html. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ^ K. Nakamura et al. (2010). "Review of Particles Physics: The CKM Quark-Mixing Matrix". J. Phys. G 37 (75021): 150. http://pdg.lbl.gov/2010/reviews/rpp2010-rev-ckm-matrix.pdf.

- ^ Z. Maki, M. Nakagawa, S. Sakata (1962). "Remarks on the Unified Model of Elementary Particles". Progress of Theoretical Physics 28 (5): 870. Bibcode 1962PThPh..28..870M. doi:10.1143/PTP.28.870. http://ptp.ipap.jp/link?PTP/28/870/pdf.

- ^ B.C. Chauhan, M. Picariello, J. Pulido, E. Torrente-Lujan (2007). "Quark–lepton complementarity, neutrino and standard model data predict θPMNS

13 = 9+1

−2 °". European Physical Journal C50 (3): 573–578. arXiv:hep-ph/0605032. Bibcode 2007EPJC...50..573C. doi:10.1140/epjc/s10052-007-0212-z. - ^ R. Nave. "The Color Force". HyperPhysics. Georgia State University, Department of Physics and Astronomy. http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/forces/color.html#c2. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- ^ B.A. Schumm (2004). Deep Down Things. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 131–132. ISBN 080187971X. OCLC 55229065.

- ^ a b Part III of M.E. Peskin, D.V. Schroeder (1995). An Introduction to Quantum Field Theory. Addison–Wesley. ISBN 0-201-50397-2.

- ^ V. Icke (1995). The force of symmetry. Cambridge University Press. p. 216. ISBN 052145591X.

- ^ M.Y. Han (2004). A story of light. World Scientific. p. 78. ISBN 9812560343.

- ^ C. Sutton. "Quantum chromodynamics (physics)". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/486191/quantum-chromodynamics#ref=ref892183. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- ^ A. Watson (2004). The Quantum Quark. Cambridge University Press. pp. 285–286. ISBN 0521829070.

- ^ a b c K. Nakamura et al. (Particle Data Group) (2010). "Review of Particle Physics: Quarks". Journal of Physics G 37 (7A): 075021. Bibcode 2010JPhG...37g5021N. doi:10.1088/0954-3899/37/7A/075021. http://pdg.lbl.gov/2010/tables/rpp2010-sum-quarks.pdf.

- ^ W. Weise, A.M. Green (1984). Quarks and Nuclei. World Scientific. pp. 65–66. ISBN 9971966611.

- ^ D. McMahon (2008). Quantum Field Theory Demystified. McGraw–Hill. p. 17. ISBN 0071543821.

- ^ S.G. Roth (2007). Precision electroweak physics at electron–positron colliders. Springer. p. VI. ISBN 3540351647.

- ^ R.P. Feynman (1985). QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter (1st ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. 136–137. ISBN 0-691-08388-6.

- ^ a b M. Veltman (2003). Facts and Mysteries in Elementary Particle Physics. World Scientific. pp. 45–47. ISBN 981238149X.

- ^ F. Wilczek, B. Devine (2006). Fantastic Realities. World Scientific. p. 85. ISBN 981256649X.

- ^ F. Wilczek, B. Devine (2006). Fantastic Realities. World Scientific. pp. 400ff. ISBN 981256649X.

- ^ T. Yulsman (2002). Origin. CRC Press. p. 55. ISBN 075030765X.

- ^ F. Garberson (2008). "Top Quark Mass and Cross Section Results from the Tevatron". arXiv:0808.0273 [hep-ex].

- ^ J. Steinberger (2005). Learning about Particles. Springer. p. 130. ISBN 3540213295.

- ^ C.-Y. Wong (1994). Introduction to High-energy Heavy-ion Collisions. World Scientific. p. 149. ISBN 9810202636.

- ^ S.B. Rüester, V. Werth, M. Buballa, I.A. Shovkovy, D.H. Rischke (2005). "The phase diagram of neutral quark matter: Self-consistent treatment of quark masses". Physical Review D 72 (3): 034003. arXiv:hep-ph/0503184. Bibcode 2005PhRvD..72c4004R. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.72.034004.

- ^ M.G. Alford, K. Rajagopal, T. Schaefer, A. Schmitt (2008). "Color superconductivity in dense quark matter". Reviews of Modern Physics 80 (4): 1455–1515. arXiv:0709.4635. Bibcode 2008RvMP...80.1455A. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.80.1455.

- ^ S. Mrowczynski (1998). "Quark–Gluon Plasma". Acta Physica Polonica B 29: 3711. arXiv:nucl-th/9905005. Bibcode 1998AcPPB..29.3711M. http://th-www.if.uj.edu.pl/acta/vol29/pdf/v29p3711.pdf.

- ^ Z. Fodor, S.D. Katz (2004). "Critical point of QCD at finite T and μ, lattice results for physical quark masses". Journal of High Energy Physics 2004 (4): 50. arXiv:hep-lat/0402006. Bibcode 2004JHEP...04..050F. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/2004/04/050.

- ^ U. Heinz, M. Jacob (2000). "Evidence for a New State of Matter: An Assessment of the Results from the CERN Lead Beam Programme". arXiv:nucl-th/0002042 [nucl-th].

- ^ "RHIC Scientists Serve Up "Perfect" Liquid". Brookhaven National Laboratory News. 2005. http://www.bnl.gov/bnlweb/pubaf/pr/PR_display.asp?prID=05-38. Retrieved 2009-05-22.

- ^ T. Yulsman (2002). Origins: The Quest for Our Cosmic Roots. CRC Press. p. 75. ISBN 075030765X.

- ^ A. Sedrakian, J.W. Clark, M.G. Alford (2007). Pairing in fermionic systems. World Scientific. pp. 2–3. ISBN 9812569073.

Further reading

- A. Ali, G. Kramer (2011). "JETS and QCD: A historical review of the discovery of the quark and gluon jets and its impact on QCD". European Physical Journal H 36 (2): 245. doi:10.1140/epjh/e2011-10047-1.

- D.J. Griffiths (2008). Introduction to Elementary Particles (2nd ed.). Wiley–VCH. ISBN 3527406018.

- I.S. Hughes (1985). Elementary particles (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-26092-2.

- R. Oerter (2005). The Theory of Almost Everything: The Standard Model, the Unsung Triumph of Modern Physics. Pi Press. ISBN 0132366789.

- A. Pickering (1984). Constructing Quarks: A Sociological History of Particle Physics. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-66799-5.

- B. Povh (1995). Particles and Nuclei: An Introduction to the Physical Concepts. Springer–Verlag. ISBN 0-387-59439-6.

- M. Riordan (1987). The Hunting of the Quark: A true story of modern physics. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-64884-5.

- B.A. Schumm (2004). Deep Down Things: The Breathtaking Beauty of Particle Physics. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7971-X.

External links

- 1969 Physics Nobel Prize lecture by Murray Gell-Mann

- 1976 Physics Nobel Prize lecture by Burton Richter

- 1976 Physics Nobel Prize lecture by Samuel C.C. Ting

- 2008 Physics Nobel Prize lecture by Makoto Kobayashi

- 2008 Physics Nobel Prize lecture by Toshihide Maskawa

- The Top Quark And The Higgs Particle by T.A. Heppenheimer – A description of CERN's experiment to count the families of quarks.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||